Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith winter nights drawing in across North America, Canadian “snowbirds” – citizens who flee their freezing temperatures for sunnier climes every year – are planning their annual trips to Florida or the Caribbean.

Traditionally, Cuba has been hugely popular among Canadians, drawn to the pristine white sands of beach resorts like Varadero.

They fill the void left by Americans wary of the travel restrictions imposed on them under the continuing US economic embargo of the largest island in the Caribbean.

Figures show that almost one million Canadian tourists visited Cuba last year, the top country of origin for visitors by some margin.

As such, a recent decision by the Canadian tour operator, Sunwing Vacations Group – one of Cuba’s leading travel partners – to remove 26 hotels from its Cuba portfolio is a blow to the island’s struggling tourism industry.

Sunwing took the decision after Cuba endured a four-day nationwide blackout at the end of October, caused by failures with the country’s aging energy infrastructure.

This was followed by another national power cut last month, when Hurricane Rafael barrelled its way across the island, worsening an already-acute electricity crisis.

A third countrywide blackout then happened on Wednesday, 4 Dec, after Cuba’s largest power plant broke down.

“Cuba has had some volatility in the last few weeks and that may shake consumer confidence,” Sunwing’s chief marketing officer, Samantha Taylor told the Pax News travel website last month.

“There are incredible places to go in Cuba,” she stressed, keen to emphasise that the company isn’t pulling out of Cuba altogether. “But we also recognise that if clients are a little uncomfortable, we need to give them options.”

Specifically, that involved drawing up a list of what they called “hidden gems” – alternative holiday destinations in the Dominican Republic, the Bahamas and Colombia.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe implications for Cuba are clear.

With tourism now the island’s principal economic motor, and the main source of foreign currency earnings after remittances, that an important tour operator is pointing its customers towards other countries’ beaches over crumbling energy infrastructure is a real concern.

“Our message to Canadians is that tourism is one of the economy’s priorities,” said Lessner Gómez, director of the Cuban Tourism Board in Toronto in a statement. “The Ministry of Tourism has been preparing for the winter season to deliver better services, uninterrupted supplies, a better airport experience, and more and new car rentals.”

While Cuba’s tourism agency tries to ease fears about the extent of the electricity blackouts, few can deny that these have been extremely difficult months on the island. Hurricane Rafael was only the latest storm to hit Cuba in a frenetic Atlantic hurricane season in which more powerful and more frequent storms are the new normal.

Of course, severe weather is a problem across the Caribbean. But for Cuba, there are other complications in play.

Donald Trump’s re-election to the White House and his choice for Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, stand to make life even more complicated for Cubans than it already is.

“This is probably the Cuban Revolution’s hardest moment,” says former Cuban diplomat, Jesús Arboleya. “And unfortunately, I see nothing on the horizon whatsoever which allows for an optimistic view of the future of US-Cuba relations.

“Donald Trump has handed US policy towards Cuba to those sectors of the Cuban American right who have essentially lived off anti-Castro policies since their origins.”

Mr Arboleya adds that Marco Rubio, currently a US Senator for Florida, is the leading voice among them. He is a Cuban American long opposed to the communist government in Havana.

His parents were Cubans who moved to the US in 1956, three years before Fidel Castro seized power, but his grandfather fled the Castro-led turn to communism on the island.

“People are horrified by the idea of another Donald Trump presidency. It spells real trouble,” echoes Cuban political commentator and editor of Temas magazine, Rafael Hernández.

Current US policy towards Cuba is “somewhat schizophrenic”, he argues.

“On the one hand, the State Department facilitates support to the private sector, and [pushes for] economic changes in Cuba. But on the other hand, Congress and Senate seem to freeze any advances on those reforms.”

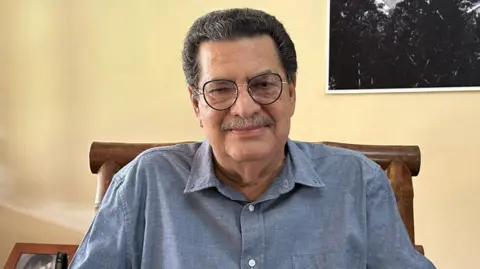

Jesús Arboleya

Jesús ArboleyaThe expectation is, however, that a future Secretary of State Rubio will coalesce the US’s Cuba policy around a single idea – maximum pressure on the island by tightening the already-harsh sanctions.

Cubans fear that could mean the suspension of commercial flights to Cuba, or even the closure of the US Embassy in Havana, which was officially reopened in 2015 after decades of frosty relations.

If implemented, such steps would be deliberately designed to further harm Cuba’s floundering tourism trade, the aim to hit the communist-run nation when it’s down. Tourist numbers to Cuba have almost halved since the high point of nearly five million visitors during the Obama-era détente with Cuba.

Between 2015-2017 US visitors flocked to the island under more relaxed travel restrictions, keen to experience a country that had long been denied them. Around the same time, the Cuban government embarked on a major hotel-building spree, confident that demand would remain strong over the next decade.

However, there followed a double blow to Cuban tourism from which it hasn’t fully recovered. First, the Trump Administration rolled back President Obama’s engagement policies, and then the Covid-19 pandemic sent the industry into freefall.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith many of those hotels now registering much lower occupancy rates than originally predicted, and real difficulties in providing the five-star customer experience as advertised amid the blackouts and shortages, some question the strategy of putting so many eggs in the tourism basket in the first place.

“Why has Cuba invested 38% [of government funds] on average over the past decade in hotels and infrastructure connected to international tourism, but only 8 to 9% on energy infrastructure?” asks economist Ricardo Torres at the American University in Washington DC. “It doesn’t make sense. The hotels run on electricity.”

Even with all the current challenges, most visitors agree that Cuba remains a unique travel experience. The cliches – classic cars, cigars and mojitos – still appeal to many, while others prefer to travel the island absorbing its history, culture and music.

Yet as tour operator Sunwings’ decision to step back shows, some tourists are finding it hard to appreciate Cuba during its energy crisis, especially if it’s about to be exacerbated by a hostile administration – and Secretary of State – in Washington.