The best seat in the house is still reserved for John Madden.

His throne is fully reclined and draped in a fleece Raiders blanket. It sits squarely before a 20-foot-tall LED wall, a study in sensory overload, showing every NFL broadcast at once.

When the Hall of Fame coach retired from the TV booth in 2009, until his death in 2021, he watched games in his own temple of boom — a family-owned production studio in a quiet business park.

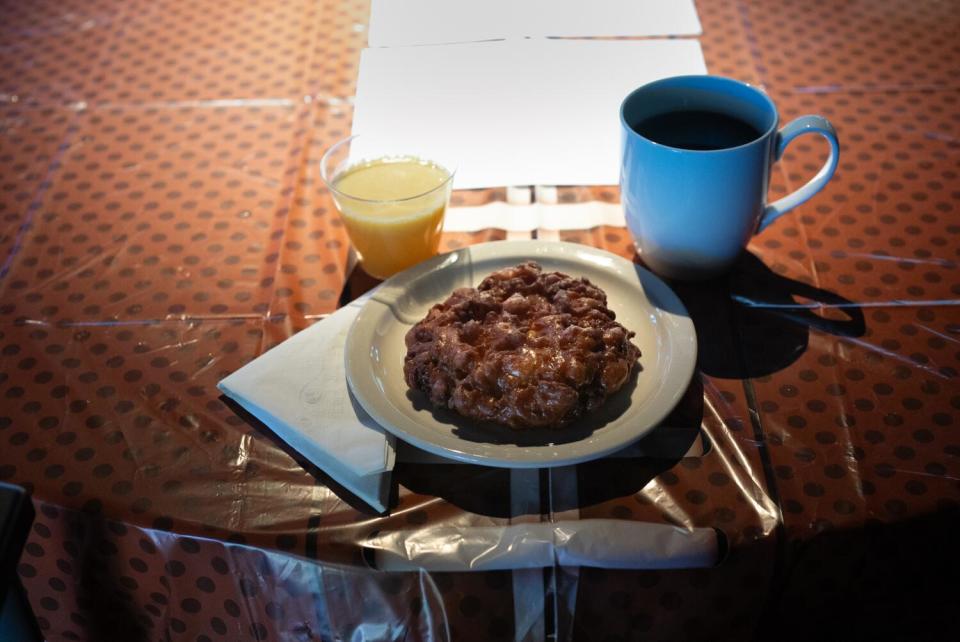

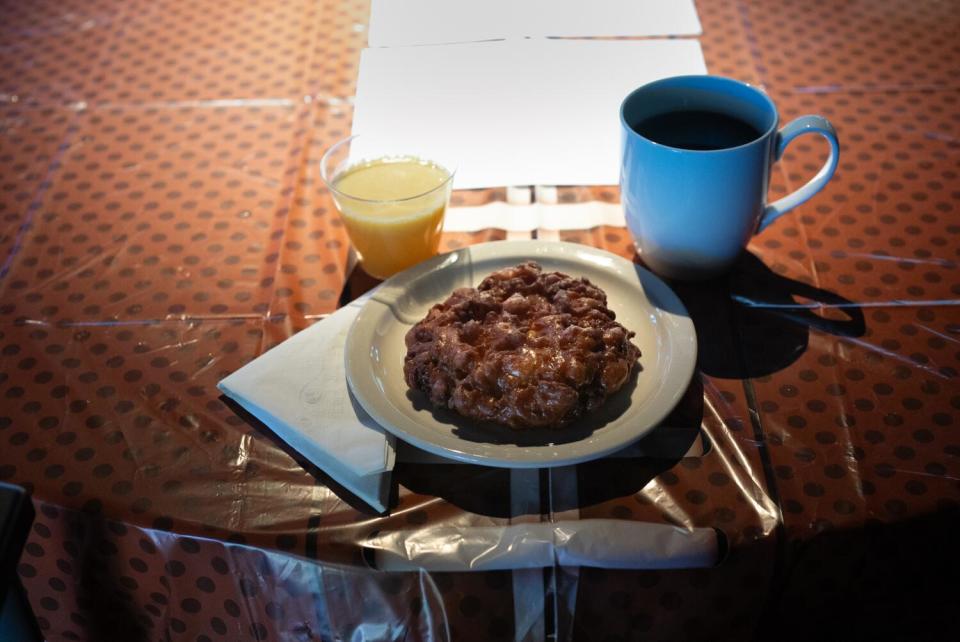

He would sit in that recliner, or at a table at the back of the darkened and cavernous room, where his family now arranges a weekly place setting in his honor. There’s a cup of coffee, a glass of orange juice and a fresh-baked apple fritter, all of which go undisturbed throughout the day.

Madden is gone, but his family and various friends still gather every Sunday to watch games on the swooping, futuristic video board, one that rivals that of a state-of-the-art stadium.

In the same building is his office, filled with memorabilia from his years as a Super Bowl-winning coach of the Oakland Raiders, illustrious career as a broadcaster, and decades as namesake of a video game that has generated billions of dollars.

“This is where he did business, but every Sunday this was our home,” said his son, Joe. “This was not an office anymore.”

Long after his retirement from broadcasting, Madden continued to impact the NFL. He was a special assistant to commissioner Roger Goodell and chaired a league panel focused on making the game as safe as it could be.

“He volunteered to be Roger’s football guy,” son Mike Madden said. “He said, ‘You’ve got your business guys. You’ve got your legal guys and your stadium guys. I want to be your guy who makes sure football stays football.’

“He’d call Roger during the games on Sunday from here. ‘Are you watching what’s going on in Cincinnati?’ He wanted to make sure the football didn’t get watered down or changed or altered.”

In an email to The Times on Sunday, Goodell wrote of Madden: “As a fan, he was legendary. Coach was remarkable. I was fortunate to have his insight, experience and support throughout my years as commissioner.”

It wasn’t just Goodell who Madden reached out to during games. He also kept in close touch with his friend, Andy Reid, coach of the Philadelphia Eagles then Kansas City Chiefs.

“He’d call Andy in the middle of a game,” said Madden’s widow, Virginia. “I’d say, ‘You can’t do that.’ He’d say, ‘Well, he doesn’t have to answer.’ He might call or text him after a play. He did that a couple of times. Sometimes, Andy would talk to him. Andy was his go-to guy. He really loved Andy.”

That’s the kind of respect that Madden commanded, especially from those people who knew him as more than a commentator who described collisions with cartoonish sounds.

“It would probably surprise people how smart he was,” Mike Madden said. “He was a coach and a teacher. Those were the common threads. The boom and the whack and doink, and the turducken and six-legged turkeys, that was kind of a schtick created by a smart guy.

“We love [comedian and impressionist] Frank Caliendo and his imitation, but he’s not that guy. Dad was a really smart guy who had that coach’s mentality pretty much with everything he did. It was, you’ve got to prepare, you’ve got to explain, you’ve got to prepare those around you, then you’ve got to execute. That was a recurring theme.”

The Sunday routine was — and still is — a regimented process. The contiguous video display was installed recently, but the display that Madden used was a cinema-sized screen in the middle bracketed by four large flat screens on each side. He would rank the games by importance then arrange them on the screens accordingly. If a moment merited it, he would move that game to the big screen in the middle.

That screen juggling was handled by a “switcher,” a human remote control who operated as a DJ of sorts. Bobby Mattos has handled that job for the last nine years.

“It was no commercials, and injuries over entertainment,” Mattos said of Madden’s instructions. “If somebody got hurt, he wanted to see it. He wanted to figure out if there was a rule or penalty or technique that could take that issue out of the game.”

Mattos still handles switcher duties, but he now does so wirelessly with a tablet, and it’s Virginia who decides at the beginning of the day which game will appear in which spot on the display.

There’s a printed “menu” for the guests that lists which games will be in which spots, and the broadcast teams working those games.

“Coach Madden would get a text on occasion from the broadcasters, and they’d want to know what screen they were on,” Mattos said. “He’d say, ‘You’re in the 1 hole.’ That was pretty cool. They wanted to be in the 1 spot.”

It’s not as if the friends invited to watch games at the studio are a collection of Hall of Famers or even people with deep NFL ties. Among the people watching Sunday, for instance, were a handyman who works with the family’s properties, two high school friends of Mike, a retired basketball coach from a local high school, and John Madden’s longtime endocrinologist.

Two of John Madden’s grandsons were there, too — Joe’s son, Sam, who helped in the construction of the massive video display, and Mike’s son, Jack, who recently graduated from Cal Poly San Luis Obispo with a degree in food science and now is beginning his graduate studies.

Although he isn’t a big football fan, Jack bonded with his grandfather over food preparation. Madden was just as exacting about that as he was about football.

“We went in with a strategy just to hit a buffet,” Jack said. “I’d give him a scouting report on what the best items were.”

That tradition continues for a viewing sessions. Sunday, the fare included steak sandwiches, spaghetti and fresh-baked chocolate chip cookies.

“As dad gave up his radio shows and commissioner’s duties, this was all he had,” Mike said. “So he had all this bandwidth and brain power, and it would get applied to this. That’s a lot of brain power for food and games.”

Family or friends, the Maddens make no distinction.

“Some families have Sunday dinners,” Mattos said. “This is one big family lunch.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.