In the fevered run-up to the most over-hyped quarterly earnings announcement in recent years—Nvidia’s, of course—it’s hard to believe that anything of relevance was left unsaid. But in fact three crucial elements of the Nvidia story were under-played or ignored. Without understanding them, envisioning the company’s future is hopeless.

Believe it or not, Nvidia’s profitability is more astonishing than you think

The company’s profit for the second quarter was a staggering 168% greater than profit for the same quarter last year. If Nividia just earned that same profit for the year’s two remaining quarters, it would be the fourth most profitable company in the Fortune 500 (behind only Apple, Berkshire Hathaway, Alphabet, and Microsoft). But Wall Street analysts expect Nvidia’s profits to continue growing strongly this year—and on average the analysts have underestimated Nvidia’s performance so far.

Even more impressive is Nvidia’s profitability on multiple measures. I have long preferred measures based on economic profit, also known as economic value added (EVA), which eliminates distortions in standard accounting. Institutional Shareholder Services calculates EVA data for 21,000 publicly traded companies worldwide, and it reports that Nvidia’s returns on capital and its upward trend put it in the 100th percentile for profitability. That doesn’t mean Nvidia is in the top percentile (which would be the 99th percentile). It means Nvidia ranks above all those other 21,000 companies, or possibly ties with some of them.

That is simply phenomenal. When Nvidia’s profit growth slows down, as eventually it must, the company could still rank in the 95th percentile—or heck, even in that shabby 85th percentile—and remain an extraordinary financial performer.

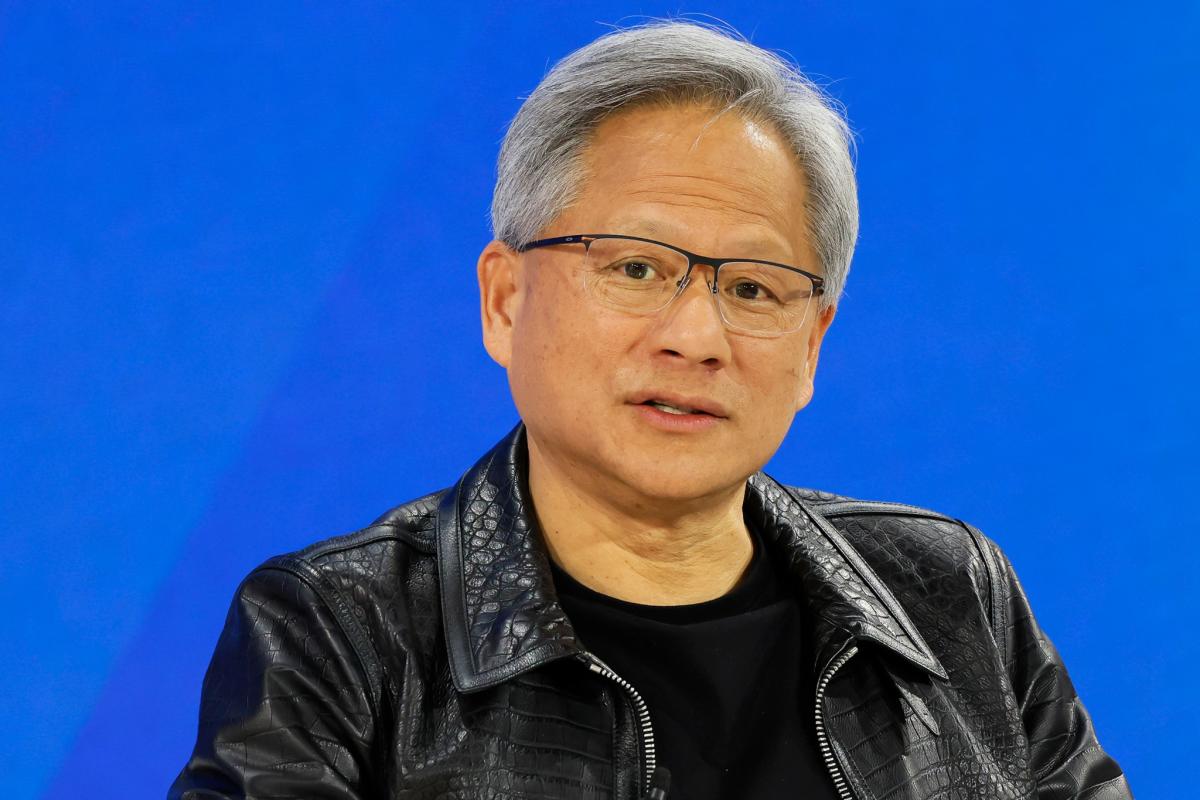

CEO Jensen Huang’s early life was tougher than you probably know, and it helps explain his successful leadership

Huang made news in March when he spoke to students at his alma mater, Stanford University. “Greatness is not intelligence,” he told them. “Greatness comes from character, and character isn’t formed out of smart people. It’s formed out of people who suffered.”

He didn’t go into much personal detail at that event, though he has often mentioned that he was a dishwasher at Denny’s, “and then they promoted me to busboy.” But he was much more open about his formative years when he spoke to Fortune 23 years ago:

In 1973, the 9-year-old Huang was living in Thailand with his Chinese parents. Worried about the political situation there, his parents decided to send him to a U.S. boarding school his uncle had found in a magazine ad. Before long Huang was enrolled in the Oneida Baptist Institute in Oneida, Ky. … It turned out the institute was a school for troubled kids. Huang’s 17-year-old roommate was fresh out of prison and covered with stab wounds. Huang says that during his two years at the school he got beat up a lot and spent afternoons cleaning the latrine. Nonetheless, he looks on those days as a valuable experience. “Now I don’t get scared often. I don’t worry about going places I haven’t gone before,” says Huang, “and I can tolerate a lot of discomfort.”

Suffering remains central to Huang’s leadership. “To this day I use the phrase ‘pain and suffering’ inside our company with great glee,” he told Stanford students. “You want to refine the character of your company. You want greatness out of them.”

Huang will wait years for his convictions to pay off

CEOs often complain that Wall Street won’t let them embark on long-term projects that will yield profits only far in the future. Huang has insisted on pursuing such projects anyway. Investors should know that Nvidia’s history is a story of spending years to create technology for which there is no market until the technology creates a market.

Nvidia’s first project was designing chips to create 3D graphics for videogames when videogames barely existed. Eventually the chips turbocharged the games industry and made Nvidia successful. Huang and his partners knew that same technology could do much more, including powering a new way of computing that became AI. But “for 10, 15 years, the markets that fuel Nvidia today just didn’t exist,” says Huang. “All your shareholders, your board of directors, your partners—you’re taking everybody with you, and there’s no evidence of a market. That is really, really challenging.”

Huang’s experience is a warning to Nvidia investors that some day after today’s AI frenzy, the time may come when they must be patient. It’s also an inspiration to business leaders that pain and suffering will yield dividends, and that persistence and confidence can pay off, sometimes spectacularly.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com