December’s Full Cold Moon shines in the sky this weekend, and due to an astronomical quirk, it may appear strangely ‘off kilter’ as travels across the sky Saturday night.

What is a Full Cold Moon?

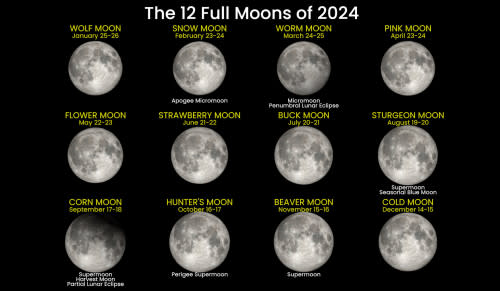

Saturday night’s Full Moon is 2024’s Cold Moon. The name is one of a dozen given to the Full Moons of the year by the various farmer’s almanacs.

(NASA/Scott Sutherland/Fred Espenak)

According to the Old Farmer’s Almanac, the names originate from Native American, Colonial, and European traditional folklore.

“December’s full Moon is most commonly known as the Cold Moon — a Mohawk name that conveys the frigid conditions of this time of year, when cold weather truly begins to grip us,” they state on their website.

“Other names that allude to the cold and snow include Drift Clearing Moon (Cree), Frost Exploding Trees Moon (Cree), Moon of the Popping Trees (Oglala), Hoar Frost Moon (Cree), Snow Moon (Haida, Cherokee), and Winter Maker Moon (Western Abenaki),” they add.

While titles such as ‘Harvest Moon’ and ‘Hunter’s Moon’ specifically refer to the Full Moon, the names taken from indigenous sources actually do not. Instead, they are the lunar calendar equivalent of the names of the months in the Gregorian calendar. Each refers to one of the roughly 29-day periods of the lunar cycle — ‘lunations’ — between one New Moon and the next. Thus, even though this year’s Full Cold Moon is on the night of December 14-15, in the 2024 lunar calendar, the Cold Moon is really from December 1 through December 30.

(NASA/Scott Sutherland)

DON’T MISS: Look up! What’s going on in the December night sky?

Full Moon Lunistice

As mentioned above, every 29 days or so, the Moon goes through a cycle of phases. This progresses from New Moon to First Quarter to Full Moon to Last Quarter and back to New Moon.

Watch closely, though, and you will notice other changes. The most obvious tends to be the Moon’s apparent size in our sky, which produces ‘supermoons’ and ‘micromoons’ due to the Moon’s elliptical orbit around Earth.

More subtle, though, are the changes in exactly where the Moon rises and sets along the horizon, as well as exactly how high the Moon reaches as it travels across the sky. These changes occur because the Moon’s orbit is tilted, not only with respect to Earth’s equator, but also compared to the path Earth traces around the Sun.

This diagram shows the Earth and Moon orientations during major and minor lunar standstills. The cycle represented by this is called the Cycle of Regression of the Nodes. (Scott Sutherland, based on a diagram by ‘Another Matt’ on Wikimedia Commons)

This results in a phenomenon known as lunistices.

Each year, the Sun goes through solstices, reaching its highest point in the sky during the summer solstice and its lowest point during the winter solstice. This occurs because of the 23.4° tilt of Earth’s rotational axis.

In a similar way, the Moon’s tilted orbit causes it to reach a highest and lowest point in our sky each month. These are known as lunistices or lunar standstills.

This diagram shows the range of moonrises during a major and minor lunar standstill. (Fabio Silva/The Conversation, CC BY-NC)

READ MORE: Heads up! A total lunar eclipse will shine across Canada late this winter season

However, due to the gravitational tug-of-war exterted on it by the Sun and planets, the Moon’s orbit slowly ‘wobbles’ around Earth. This sets up two types of extreme lunar standstills, each of which occur far less frequently.

Major lunar standstills — when the Moon rises and sets at either the farthest northerly or farthest southerly point along the horizon — happen once every 18.6 years. Roughly halfway in between, we see minor lunar standstills.

We saw the southernmost major lunar standstill during this year’s Full Strawberry Moon. On that night, researchers gathered at Stonehenge, the famous megalith located on Salisbury Plain, in the south west of England, to determine if the stones placed around it not only track solstices, but also these lunistices. Their investigation will conclude in 2025, after the current cycle of major lunar standstills ends.

This weekend, specifically on Saturday night, we will see the northernmost rise of a Full Moon since 2006. The Moon will then make its highest pass through the sky throughout the night, and set at its farthest northerly point along the horizon Sunday morning.

A split simulation of the night sky shows both the December 14 Full Cold Moon (left) and the June 20 Full Strawberry Moon (right), as the northernmost and southernmost moonrises. (Stellarium/Scott Sutherland)

After this, due to the Moon’s orbit continuing its slow wobble around Earth, we won’t see these kinds of extreme Full Moon lunistices return until 2043.

(Thumbnail image courtesy Silvia Porras, who snapped this picture of the 2022 Cold Moon from Toronto, Ontario)