First Nations have a longstanding tradition of welcoming guests into their communities, with that hospitality deeply rooted in a culture of respect and sharing.

Whether it’s for work, love or travel, some guests end up staying for decades, or even a lifetime.

For these non-Indigenous people who have put down roots in First Nation communities in Ontario, reconciliation takes on a personal meaning.

Reconciliation is a process that aims to address the historic address the historical injustices and ongoing impacts of colonization, particularly the legacy of residential schools and systemic discrimination against Indigenous communities.

Three non-Indigenous people who have built a life in First Nations describe what reconciliation means to them on an individual level.

Émilie Veilleux: ‘I just fell in love with the community’

Originally from Quebec, Veilleux was working as an outpost nurse in different remote communities when she decided to permanently relocate to Peawanuck, a Cree community on the Winisk River in northern Ontario.

“I just fell in love with the community, with the people,” she said. “It became my safe place.”

She talks about how, almost a decade ago, a friend from the community brought her to Hudson’s Bay.

“I remember standing there, looking around me, feeling so at peace, so happy.”

Émilie Veilleux thinks non-Indigenous people need to go out on the land and eat local foods to better understand the community, especially when they are administering funding programs for different services. (Submitted by Emilie Veilleux)

Veilleux ended up meeting someone and found work with the local band office. She’s now Peawanuck’s director of health and one of the only non-Indigenous people living in this community of about 250 people.

Veilleux said that at times, she feels the weight of history in her day-to-day life.

“I know for some people, they will see me and it might bring back trauma,” she said. “I’m aware of that and it’s not their fault… it’s the reality.”

She believes she has a small part to play in reconciliation by using her experience to get more funding for the community.

She said she’s noticed how some non-Indigenous people travelling through Peawanuck — especially ones doing assessments on behalf of the government — don’t take the time to eat local foods, stay in local homes or travel out on the land during their stay.

Émilie Veilleux says truth and reconciliation is an important topic to discuss with her young family. (Submitted by Emilie Veilleux)

“But it’s the only way to understand what people go through every day… Like go out and see for yourself,” she said. “We need to listen to Indigenous people… they are owed that.”

Veilleux said she wishes she had learned about Canada’s past growing up and hopes to carve out a different education for her own family members, some of whom have both Quebec and Cree identities.

“It’s important to be truthful and honest about history,” she said.

Chris Mara: ‘A place where I felt I was more comfortable’

“I’m an outsider — I’m not a community member, I’m not Indigenous. But being welcomed in Wiikwemkoong has been an incredible part of my life,” said Mara, who has taught math and sciences at the community’s high school for more than 25 years.

He’s now a “nimishoomis teacher,” meaning he’s teaching the children of children he’s taught.

“My whole life has been seeing the young people of Wiikwemkoong be successful,” he said.

Mara grew up in the Kitchener-Waterloo area and initially came to the north shore of Lake Huron as a Jesuit missionary. During that time, he said, he had profound experiences learning about the connection between spirituality and the land from elders in Sagamok and Wiikwemkoong.

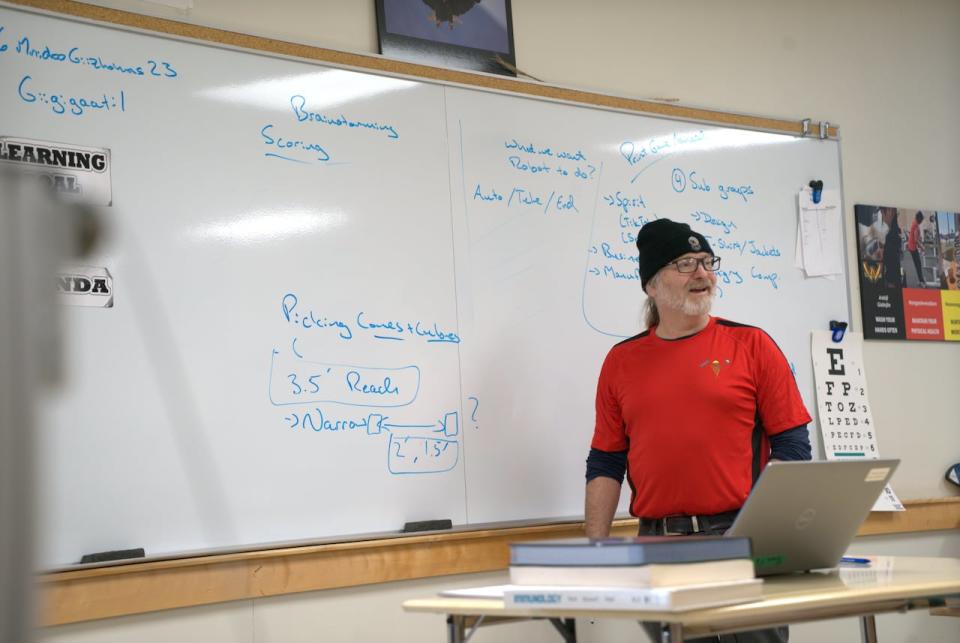

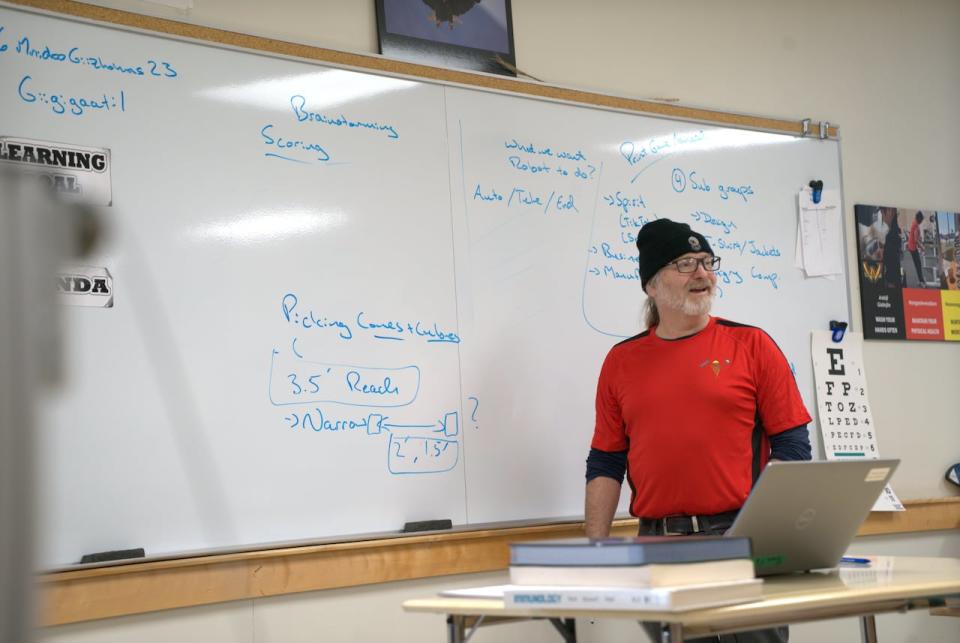

Chris Mara has been teaching at the Wikwemikong High School for more than 25 years. He’s been involved with the Robotics team there as they’ve competed on the national stage. (Aya Dufour/CBC)

In search of community, he ended up leaving the religious order he was a part of and went on to become a teacher. He eventually got a call from Wiikwemkoong about an opening at the local school.

“It just became a place where I felt I was more comfortable, more at home than anywhere else,” said Mara.

For him, reconciliation means giving back something of what he’s been given over the years. It means reflecting on those who have passed on and their stories.

Chris Mara is pictured doing sketches during a planning session of the Wiikwemkoong High School robotics club. (Aya Dufour/CBC)

“There’s got to be a better term than reconciliation,” said Mara.

“It implies two sides that have done something wrong to each other … First Nations don’t have anything to reconcile. It’s non-Indigenous people that need to do the work.”

He said he still sees gaps between the community that adopted him and similar non-Indigenous communities, and doesn’t understand why.

He wants to see Indigenous sovereignty, especially over traditional lands.

“My students will make amazing leaders. Many of them already are.”

Bruce Mills: ‘Anishinaabe people are my family’

Mills’s life has been intertwined with that of his Anishinaabe neighbours for as long as he can remember.

Growing up in the small town of Thessalon near Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., he went to school and played sports with folks from nearby Thessalon First Nation. He then ended up falling in love with a community member with whom he will soon be celebrating 46 years of marriage.

They recently moved to the community to be closer to their children and grandchildren.

Mills said he’s been reflecting more on what it means to be white in an Anishnaabe family after visiting the residential school in Kamloops.

“It was such an eerie feeling,” he said, adding it’s hard to describe. “It just doesn’t feel right.”

He doesn’t believe an apology and an acknowledgment of what Indigenous people suffered will be enough to fix things.

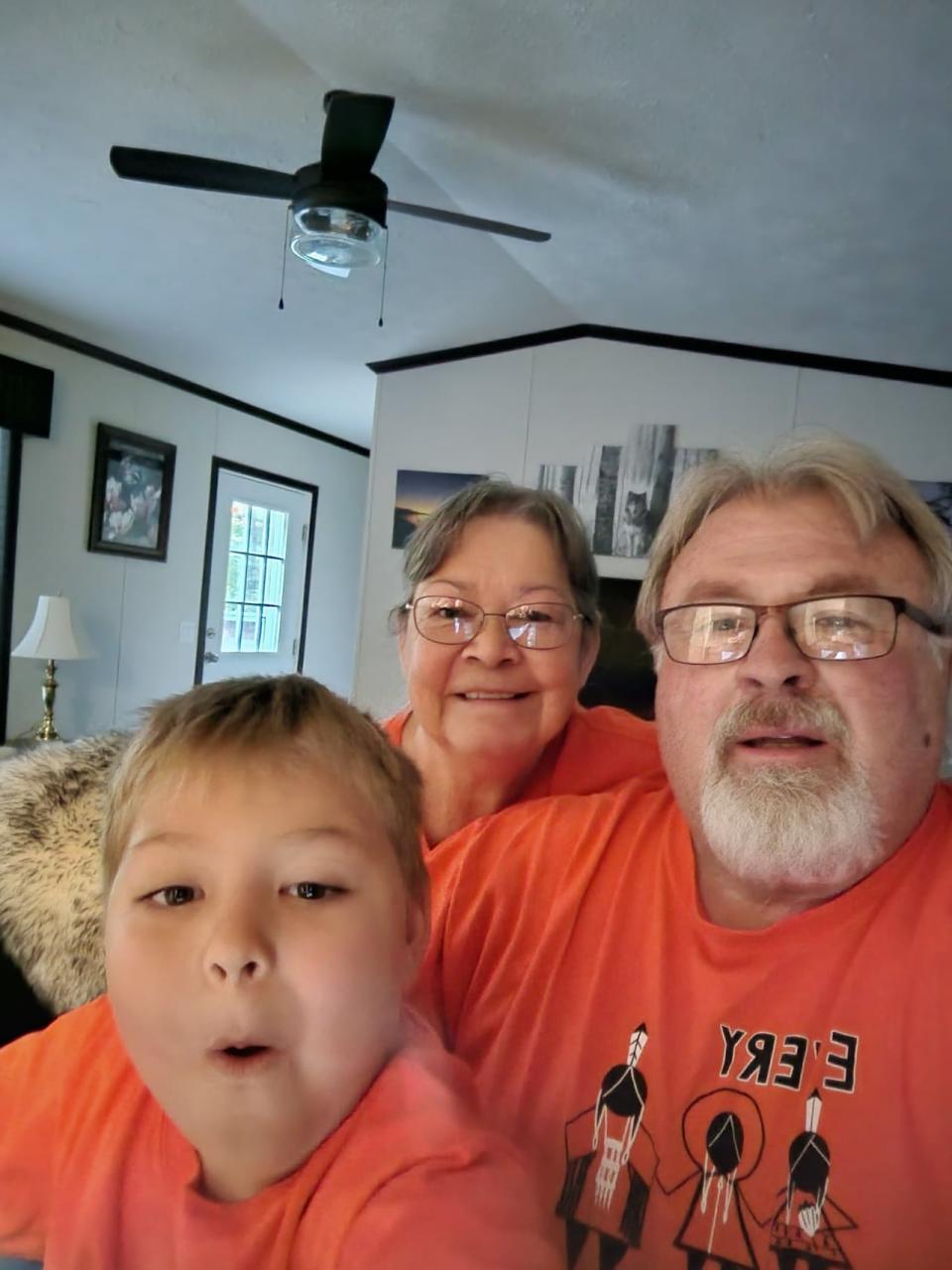

Bruce Mills and his partner, living on Thessalon First Nation, have signed up to be foster parents in their late 60s. (Submitted by Bruce Mills)

“This will never go away… People need to be educated to understand this,” he said.

Mills said he sees the legacy of colonialism in his own family, pointing to mental health and addiction problems.

At 67, he and his partner are back to being parents through an Indigenous foster-care program. Raising him in Thessalon First Nation, in Anishinaabe culture, is one of the ways he sees his role in reconciliation.

“I’m not part of the problem — my white status is a problem. That’s where it all started, not necessarily through me, but through colonialism, which I’m part of. This is how I give back,” he said.

“Anishinaabe people are my family and I would fight with them until death.”

All three tell CBC they are hopeful that non-Indigenous Canadians are starting to be more aware of the legacy of residential schools. They believe, however, that the society is still far from being equitable and just for all Canadians.