Warning: this story contains distressing details.

A couple who reconnected, fell in love and got married decades after being at the same residential school are now sharing their stories to make sure the truth of what happened is never lost.

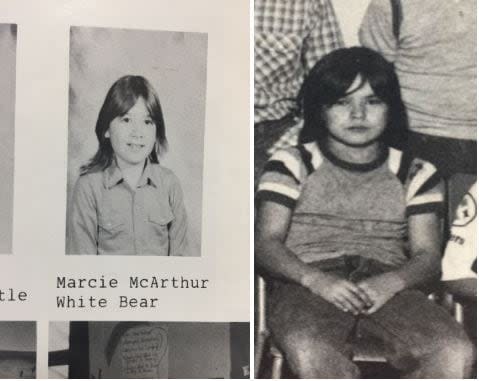

It’s been more than 30 years since Tony Stevenson and Marcie McArthur-Stevenson were classmates at the Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School (QIRS) in Lebret, Sask. Open from 1884 to 1998, it was one of the longest running residential schools in Canada.

McArthur-Stevenson first went as a Grade 3 student in 1979, when she was eight. Stevenson came to the school as a Grade 5 in 1981, when he was 12 years old, and was in the same class as McArthur-Stevenson’s older sister.

Marcie McArthur is from Pheasant Rump Nakoda Nation and Tony Stevenson is originally from Cote First Nation and a part of the Anishinaabe First Nation. (Submitted by Tony Stevenson)

After they left the school, they traveled different paths.

McArthur-Stevenson moved to Brandon, Man., and started a family. She had two boys and two girls.

“When I graduated, I never looked back, I never talked about anything,” McArthur-Stevenson said.

Stevenson went to university, but said the trauma stemming from sexual abuse he suffered at the Lebret school caused him to spiral and he didn’t finish.

“Unfortunately, I was going through a rough time, a rough patch in life, because I went to the Crown prosecutor to press charges against the pedophile that I’d come across, who was an employee of the residential school,” Stevenson said.

“It caused a lot of dysfunction with my growing up.”

After decades apart, Stevenson and McArthur-Stevenson met again in 2017, when he came to see her father in the hospital to help the older man appeal his residential school settlement claim.

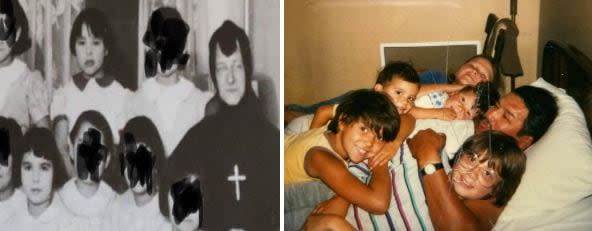

Tony Stevenson’s mom, bottom left, attended the Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School, as did Marcie’s dad. (Submitted by Tony Stevenson and Marcie McArthur-Stevenson)

Stevenson’s mom and McArthur-Stevenson’s dad had also attended the Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School.

“I was waiting there with dad and [Stevenson] walked in. He just looked at me and he’s like, ‘Marcy. Little Marcy,’ because I was small in school,” McArthur-Stevenson said with a laugh.

Stevenson was working as an agent for two law firms in Regina that were acting on behalf of survivors. He said he came across many fellow residential school classmates through the process.

“It was sad, because there were a few that got their cheque and once they got it, they died,” Stevenson said. “They OD’d, lived the harsh life, and they just didn’t wanna be here anymore.”

After the hospital meeting, the two reconnected.

McArthur-Stevenson said she was struck by how comfortable her dad was talking to Stevenson about his residential school experience, something he never shared with his own children. McArthur-Stevenson said she thought if her dad felt comfortable with Stevenson, so could she.

Their relationship moved past just being old classmates.

“I shared things with him I never talked to anybody about, I think because of what he shared with me,” McArthur-Stevenson said.

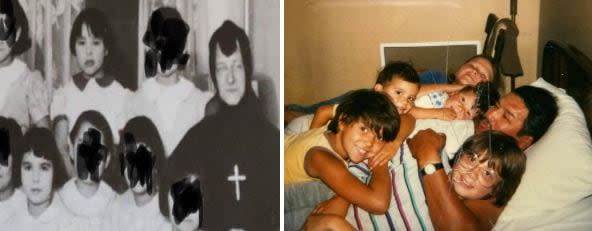

They were married three years later, on Sept. 10, 2021, and now live together in Brandon.

Tony Stevenson and his wife Marcie McArthur-Stevenson reconnected in 2017, more than 30 years after they left the residential school in Lebret. (Submitted by Tony Stevenson)

MJ’s Ole Skool Crew

In 2018, a friend asked the couple to do a presentation on residential schools and their own experiences for some students.

After hearing positive feedback, they decided to continue the work. They now give presentations under the name MJ’s Ole Skool Crew.

Stevenson said it was tough at first, but got easier because they know they are doing something positive.

He said its harder for a First Nations man to talk about sexual abuse, especially to the public. He is glad he has a partner who shares his experience and understands.

“Many times I wanted to break down, then I turn around and look at her, and she gives me the mental telepathy and I’m back on track,” Stevenson said.

He said their presentation is pure truth and honesty. They try to break negative stereotypes about First Nations people.

“You know, ‘the lazy drunk gets everything for free,'” Stevenson said as an example of these falsehoods.

The couple said they share stories from residential school survivors, telling it like it is.

“The idea is not to blame, not to point the finger. It’s to create a positive dialogue.” said Stevenson. “We’re here to teach you the history.”

Stevenson said the only issues that come up during their presentations are from some older white men.

“They just have their attitude. ‘Why didn’t you just tell somebody? Why is that my problem?'” Stevenson said.

He talked about a presentation they gave in a small town school after being invited by the principal.

“I met with her beforehand, I said ‘it’s going to be kind of hard for what we’re presenting,'” said Stevenson.

Stevenson said they got the OK to go ahead with their usual presentation.

“Some of the parents were getting a little upset, they were saying it was really harsh for them,” Stevenson said. “The answer to that is, ‘the kids in the residential schools didn’t have a say in what happened to them.'”

Tony Stevenson gives a presentation to the Law Society of Saskatchewan at the Delta Hotel in Regina, Sask. (Louise BigEagle/CBC)

Stevenson they stay as long as two hours after presentations, answering questions and getting feedback. He said some of the participants don’t want to ask hard questions in front of everybody else, but said he tells them you have to be honest, and get the harsh truth, to move forward.

“I’m glad because a lot of the old people were able to open up and speak about their abuse, and feel confident and not scared,” said Stevenson.

“I’m still carrying on their story, their legacy.”

They hope to one day be able to take their presentation across Canada, but lack funding. For now they do their presentations for organizations that invite them.

Last week they spoke to the Law Society of Saskatchewan, sharing the history of Indigenous peoples and the schools with lawyers and future lawyers.

“The idea is to get to the children, get to the high school, universities and communities. There are people out there who want to embrace this and be more proactive,” Stevenson said.

“Most importantly, we want to honour our residential school family, the ones that are not here.”

Support is available for anyone affected by their experience at residential schools or by the latest reports.

A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for survivors and those affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866-925-4419.

Mental health counselling and crisis support is also available 24 hours a day, seven days a week through the Hope for Wellness hotline at 1-855-242-3310 or by online chat at hopeforwellness.ca.